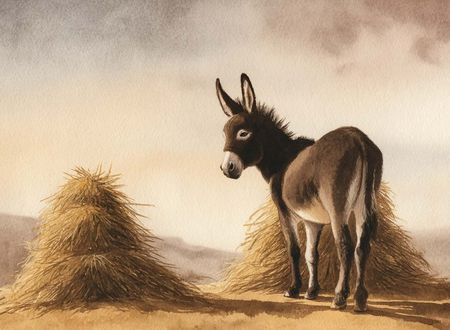

There is an old story about elephants in captivity. When they are young, trainers tie them with a rope to a small stake in the ground. The baby elephant pulls and tugs, but cannot break free. Eventually, it stops trying. Years later, that same elephant, now weighing several tons and capable of uprooting trees, remains bound by the same flimsy rope. It has learned to be helpless.

Now then, you’d think that we’d be smarter, right? Not quite.

In a fascinating experiment, a psychology teacher demonstrated something profound to her students. She gave her class what appeared to be a simple task: solve three anagrams, that is, rearrange the letters in the words given to them to form new words (e.g, cat = act.)

When she asked them to solve the first word, on one side of the room, hands shot up almost immediately. On the other side, students stared at their papers, brows furrowed, erasing and rewriting. The teacher moved on to the second puzzle. Again, half the room solved it quickly. The other half grew visibly frustrated. Some slumped in their chairs, others exchanged bewildered glances.

When she gave the third puzzle, the students who had been raising their hands earlier solved it just as swiftly and confidently.

But the other group, equally intelligent, assigned randomly to their seats, sat paralyzed. One group seemed like the clear winner. The left half of the class.

When the teacher asked the right half what they were feeling, their responses were revealing: “I felt stupid”, “I felt rushed”, “I was even more confused [because everyone else was getting it]”, “Frustrated”, “My confidence was shot” etc.

Same puzzle. Same brains, but vastly different outcomes. What happened?

Here was the twist the students didn’t know: the first two puzzles given to each half were different. The left half had received solvable anagrams like bat and lemon while the other group had received such impossible ones as whirl and slapstick.

In just five minutes, using nothing but unsolvable puzzles, the teacher induced what psychologists call learned helplessness.

It is a psychological phenomenon where, after repeated failures or exposure to uncontrollable situations, a person (or animal) stops trying, even when circumstances change and success becomes possible. The mind, having tasted defeat, begins to expect it everywhere. Like a wound that never healed, it flinches at even the possibility of pain.

As the teacher said, that learned helplessness isn’t just limited to academic tasks. It seeps into our social lives, our relationships, our very sense of self.

This is both terrifying and liberating. Terrifying because it shows how quickly our minds can be conditioned. Liberating because it proves that our limitations are often not about our actual abilities but about what we’ve come to believe about them.

They say what doesn’t kill you makes you stronger. I know, I know, they never mention the awkward middle phase where it just makes you want to eat ice cream and avoid phone calls. Humor aside, no matter what it is that you wish to do, simply don’t consider the possibility of ”I can’t do this”.

Because when we say “I can’t do this,” we are not just having a thought, we are laying down neural pathways. We are training our brains. We are, quite literally, programming ourselves for future failure. And we can’t possibly know what it is that we can or can’t do until we give our heart, mind and soul to it, until every last drop of blood in our body is offered to that pursuit.

Come to think of it, we must be the oddest creatures in the universe. For, we spend years learning to walk as babies, falling down, bumping our heads, crying, and getting back up, but as adults, if we try a new hobby and aren’t an expert in 20 minutes, we say, “Oh, this isn’t for me.”

Imagine if babies had learned helplessness (they probably would if they could understand our language). You would have a nursery full of infants sitting quietly, thinking, “Well, I tried standing up once on Tuesday and fell. Clearly, walking is not in my destiny. I shall crawl for eternity.”

The mind is very convincing when it tells you that something cannot be done. It brings evidence, it brings logic, it brings the memory of every past failure.

But you know what, the mind lies. Not maliciously, it genuinely believes it’s protecting you from disappointment. It lies nonetheless. And the only way to catch it in its lie is to try one more time.

And I’m not saying that we should keep trying because success is guaranteed. (Nothing can guarantee success, we can only increase the odds.) Not because positive thinking magically transforms reality. But because in the very act of trying, you are already defying the helplessness. You are already proving it wrong. The outcome matters less than the orientation of our soul.

A pupil went to Mulla Nasrudin after failing the same exam three times.

“Mulla,” he said with much trepidation, “I don’t think I deserve a zero on this test.”

“I agree,” Mulla replied. “But unfortunately, that’s the lowest grade I’m allowed to give.”

That student could have given up. But he didn’t. He took the exam a fourth time. And failed again. Some stories don’t have happy endings just as not every pursuit of ours will lead us to glory. That can’t be the reason to give up though (at least, not in my book). We would never know what we were meant to do, we would never discover our purpose, our potential if we hang up the boots and retreat into our shells.

All it takes to muster that courage is the realization (plus the discipline and thick skin) that the elephant doesn’t need to uproot trees to be free. It simply needs to lean against the rope once, just once, to discover that the rope has no power.

Lean against the rope that ties you, and you might be surprised at how easily it gives way. Remember, the third puzzle was always solvable…for everyone.

Peace.

Swami

A GOOD STORY

There were four members in a household. Everybody, Somebody, Anybody and Nobody. A bill was overdue. Everybody thought Somebody would do it. Anybody could have done it but Nobody did it.

Don't leave empty-handed, consider contributing.It's a good thing to do today.

Comments & Discussion

214 COMMENTS

Please login to read members' comments and participate in the discussion.