As I sit down to write this post, rain is pounding against the windows like it’s determined to barge in and trespass on my personal space. Sorry, but I’m not entertaining visitors at this time, I say. Normally the trees would sway gently in similar conditions, but right now they seem rather terrified, as if trying to duck the onslaught. The skies seem to be not just unloading the heavy clouds but ranting with the near constant lightning.

And yet in all this, the raindrops are quietly sliding down my window as I look out. Pitter-patter and then they quietly glide down the windowpane. Pitter-patter and another silent slide against the glass. Numerous very tiny insects and creatures that had been doing an aggressive tornado-like spin on the grass not more than thirty minutes ago have all but disappeared. A few dead ones are lying like dust on the water collected at the windowsill outside.

Looking at the death and destruction of millions of tiny insects and other living beings, observing how the rain and storm seem hell-bent on annihilating the trees, I find myself returning to a question that has haunted philosophers since ancient times: Is it better never to have been born? What is the purpose, if any?

You learn everything from scratch, work hard, put your life together, you fall in love, you fall out of love, you grow older, your knees hurt, people you love leave, and in the end, you leave too. There’s a strange joke in all of it. Wouldn’t it be better if we were never born?

This isn’t melodrama. It’s a serious philosophical position called antinatalism, and before you dismiss it as pessimistic nonsense, consider that some of humanity’s clearest thinkers have wrestled with this very question.

Seems like our seers understood it all too well. Otherwise, why would the Vedas encourage each individual to work toward salvation so they are never born again? I am not saying that life is bad but for most people it is unsatisfactory. In the sense that it never fully gives you what you hope it should. I mean no matter what you have, our consciousness is predisposed to discover something that’s lacking.

I remember trying to read Arthur Schopenhauer’s The World as Will and Representation many years ago and distinctly remember not finishing even the first volume. But I do recall bits of it (paraphrased). He contended that life was a mistake. That existence itself was suffering, driven by an endless and blind will to live. Every desire, he said, is suffering until it is fulfilled. And when it’s fulfilled, it leaves behind boredom — which is just suffering wearing a different mask.

Between Schopenhauer and the more contemporary, David Benatar, it’s hard to say who should win the prize for the gloomiest philosopher of all time. If they ever met at a party, they’d probably argue about whether it was worse to have been invited or to have shown up. But, I’d like to quote Benatar from Better Never to Have Been: The Harm of Coming Into Existence:

While good people go to great lengths to spare their children from suffering, few of them seem to notice that the one (and only) guaranteed way to prevent all the suffering of their children is not to bring those children into existence in the first place.

Benatar says that the very nature of procreation is cruel and irresponsible. He argues there’s an asymmetry in how we think about pleasure and pain. The absence of pain is good, even if there’s no one to enjoy that absence. But the absence of pleasure? That’s only bad if someone exists to be deprived of it. By this logic, non-existence wins every time. The unborn miss nothing because they don’t exist to miss it.

Think about it this way. We don’t mourn for the countless potential people who were never conceived. We don’t hold vigils for the children we decided not to have. Their nonexistence doesn’t trouble us because, well, they never were. Yet once someone exists, they’re thrust into a world where pain is inevitable and suffering mostly assured, while happiness is, at best, intermittent and uncertain.

Even in everyday life, we acknowledge this truth obliquely. When someone dies after a long illness, we say they’re “at peace now” or “they are in a better place” or “their suffering has ended.” We recognize that nonexistence can be preferable to a life of pain. We even celebrate it in small ways. “Thank God it’s Friday” is basically admitting five-sevenths of our life needs escaping from. We call it “falling” asleep, as if consciousness itself were a cliff we’re relieved to tumble off each night.

And yet we rarely extend this logic to its natural conclusion: if nonexistence can be better than a painful existence, and if all existence contains suffering, then perhaps nonexistence is always preferable. Shouldn’t it?

But here’s where things get interesting. The very fact that we can contemplate this question, that we can step outside our immediate experience and evaluate existence itself, suggests something profound about human consciousness. We’re perhaps the only beings who can judge whether being is worthwhile to begin with. A strange privilege, if you can call it that.

When I look at life without the filter of thought, without philosophy and argumentation, what do I see? I see sincere seekers trying to discover themselves. I see parents praying for the well-being of their children and going all out to do the best they can. From a father teaching his daughter to ride a bicycle to a mother singing a lullaby, love perhaps permeates more strongly than pessimism.

I see suffering, yes, but also something else—deep love, empathy and, altruism.

Having said that, the next time you see a couple desperate to have children, or parents pushing their grown-ups to marry, or if you are simply thinking of bringing a soul into this world, do think about it: what’s the point?

And at any rate, I’m not suggesting that you take a position one way or another. I’m simply saying that at least have the courage to reflect on the thesis. Approach it merely as a philosophical inquiry if you want. We should have the courage and wisdom to entertain any thought without the compulsion to see it through. To go back to the beginning: Is it better never to have been born?

A philosophy professor specializing in antinatalism discovers his wife is pregnant. Panicking, he rushes to his mentor.

“Master, I’ve spent years arguing that existence is suffering, that nonbeing is preferable to being. Now I’m going to be a father. What should I do?”

The master thinks for a moment. “Well, you could always teach the child philosophy.”

“How would that help?”

“They’ll spend so much time wondering whether they should exist, they’ll forget to notice that they do.”

So maybe the question isn’t whether we should have been born. We’re here now, after all, and that ship has sailed. The question might be: given that we exist, given that we’ve been thrown into this strange business of living without our consent, what do we do with this uninvited guest? (Hint: I’ve written 500+ posts on it.)

Oh, I have been so engrossed in my writing that I barely noticed that the rain has stopped. The world outside my window glistens with a light that will fade soon enough. Beautiful and temporary, like everything else. Make of that what you will.

Peace.

Swami

A GOOD STORY

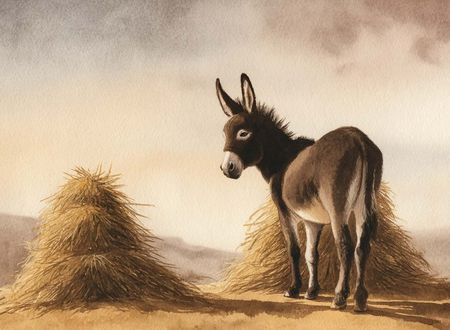

There were four members in a household. Everybody, Somebody, Anybody and Nobody. A bill was overdue. Everybody thought Somebody would do it. Anybody could have done it but Nobody did it.

Don't leave empty-handed, consider contributing.It's a good thing to do today.

Comments & Discussion

216 COMMENTS

Please login to read members' comments and participate in the discussion.