The Sanskrit term for solitude is ekānta. It is the hallmark of a person who has turned inward — their love for solitude.

An unmistakable sign of a restless mind is its inability to embrace ekānta. For the quiescent mind nothing is as profound as ekānta, and for the restless, nothing is more terrifying. There are only two types of people who are comfortable in ekānta: the lazy and the yogi.

By solitude, I do not mean that you live in a remote place but have access to TV, books, internet and the rest of it. By solitude, I mean that you are just by yourself. You in your own company. The only person you have to talk to you is you, the only person you have to listen to is you, the only person around is you. The only object of engagement for your mind is you. When you are bored, you go back to yourself and when you are happy, you share it with yourself. During the practice of ekānta, you do not even see others, let alone meet them or talk to them. The only person you get to see is you.

Ātmanayēvātmanā tuṣṭaḥ stithprajñastaducaytē (Bhagavad Gita 2.55) The one who dwells within and is contented within is indeed a yogi. The seeker who has turned inward finds the greatest bliss in solitude. In such a state, he can uninterruptedly enjoy the bliss within.

If you are in solitude and have engaged your mind in reading, writing or other similar activities, that is still solitude. However, it is not the finest type; it is more like pseudo-solitude. The ultimate ekānta is when you are aware of each passing moment, you are not dull and you are not sleepy, you are awake and alert, and, at that, you do not feel restless; you do not feel the urge to always do ‘something’. You are at peace within. When you are face-to-face with your own mind, sharply looking at it directly, you are in solitude. The one who has mastered the art of living in ekānta, such a yogin will always, without fail, be in solitude even amidst the greatest crowd. His quietude remains unaffected by the noise outside. His inner world stays insulated from the outer one.

Yōgī yuñjīta satatamātmānaṁ rahasi stithaḥ. Ēkākī yatacittātmā nirāśīraparigrahaḥ. (Bhagavad Gita 6.10) The one aspiring to attain union of the individual and Supreme soul, freeing himself from desires, clinging, and proprietorship, should turn within and meditate by dwelling in solitude.

In ekānta, after initial periods of restlessness and stupor, bliss starts to flow through your very being. Everything becomes still. Your mind, senses, body, surroundings, flowing river, waterfalls, everything — absolutely everything becomes still. The unstruck sound and beautiful other sounds start to manifest themselves. However, they can cause a deviation. A good meditator continues to stay disciplined and focused. Living in solitude requires great discipline. And with self-discipline, you can achieve just about anything you can imagine. Disciplined living in ekānta is tapas, an austerity, in its own right. It is the quickest way of self-cleansing.

Kāyēndriya sid'dhiḥ aśud'dhikṣyāta tapasaḥ. (Patanjali Yoga Sutras, 2.43) Self discipline burns away all afflictions and impurities. This has been my personal experience as well. Solitude can teach you really fast without preaching.

Yogic and tantric texts lay great emphasis on acquiring the ability and stillness to live in solitude. The great Tibetan Yogi, Jetsun Milarepa, devoted his whole life to carrying out the instructions of his guru by meditating in terrifying solitude on forbidden peaks. He was once invited by his female disciples to their village for preaching. Their argument predominantly being that Milarepa’s presence and grace, with his vast store of tapas, would help humanity, especially if he could be among and around them in the cities and villages.

Milarepa, however, committed to the practice of meditation, replied, “Practising meditation in solitude is, in itself, a service to the people. Although my mind no longer changes, it is still a good tradition for a great yogi to remain in solitude.” 1

As part of mental transformation, the practice of ekānta is critical. The practice of solitude, naturally, incorporates the practice of observing silence as well. You can start the practice of ekānta, by opting for short periods first with a minimum stretch of twenty-four hours. For towners, it is extremely hard to find solitude.

To begin with, you can find yourself a quiet room and lock yourself in it for a day or so. Take frugal provisions with you. Your room should ideally have an attached washroom. Please be aware that this is a beginner’s level. Gradually and steadily, the intensity of solitude is increased by practicing it in truly isolated places and secluded spots. My own experience says that as you progress, Nature arranges everything for you including spots for such meditation.

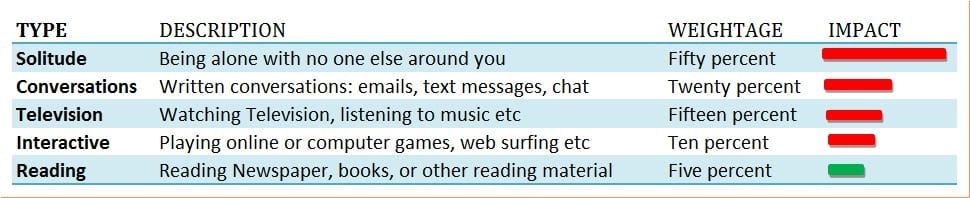

Please refer to the table below to understand the definition of good solitude:

During your practice of ekānta, having any company or coming to face-to-face with anyone is an instant failure item (read Mauna for more on this term). That nullifies your practice of ekānta. You need to start again. The same goes for interactions, watching TV, web surfing.

The practice of ekānta is even stricter than the practice of observing silence. The only discount you have is the allowance to read something. Although that too affects your solitude but it is still acceptable. The goal is to learn to have your mind free of all engagements. I am eager to share my own experiences in Himalayan solitude, however, my posts become really long when I do that. I am hoping to document them separately one day.

Go on! Learn to free yourself from the crowd, so you may learn to be free when crowded.

Peace.

Swami

Notes

A GOOD STORY

There were four members in a household. Everybody, Somebody, Anybody and Nobody. A bill was overdue. Everybody thought Somebody would do it. Anybody could have done it but Nobody did it.

Don't leave empty-handed, consider contributing.It's a good thing to do today.

Comments & Discussion

18 COMMENTS

Please login to read members' comments and participate in the discussion.