It was towards the end of February 2011. At an altitude of 10,000 feet, in a Himalayan forest, with icicles hanging outside from the thatched roof, I sat in intense meditation. Ten hours of perfect stillness of the body and mind had passed as easily as the night turns to dawn.

The soft beams of the full moon landed on the Sri Yantra, a mandala, in front of me. This mandala was a geometrical representation of kundalini or Mother Divine and was an integral part of the meditation I was doing at the time. In that hut, there were enough fissures and holes letting light and air enter how they pleased. It was a magnificent sight, to have the center of the mandala light up with a moonbeam.

I had drawn it on paper with a pencil and had used that simple piece of paper for seven months. The small rundown hut was plunged in darkness but for the moonlight that lit up the yantra most mystically, if not mysteriously. I’d started at 5PM and it was 3AM by now. It took me years to get here, a stage where I could sit in one posture for as long as I needed without affecting the lucidity of my meditation or the sharpness of my concentration.

I whispered my prayer thanking God, various energies and the forces of nature for allowing one more day of sadhana. Devoting my meditation to the welfare of every living being, I performed ten mudras, handlocks, to channelize the energy gained from the intense practice. The rats in the hut dashed around in all directions, as if they knew it was my time to get up and theirs to get off my asana, seat.

I used to sit, meditate and sleep in the same place. Three wooden planks laid next to each other formed my bed of 3×6 feet on the muddy floor. On those planks was a thin cotton mattress. On that mattress was one blanket. And on that blanket was a pillow. That’s where I sat and meditated for seven months, averaging 20 hours a day. Most days I meditated between 18 and 22 hours. Following a strict regime of starting my roster of meditation at the same time, day-in day-out I carried on with my practice.

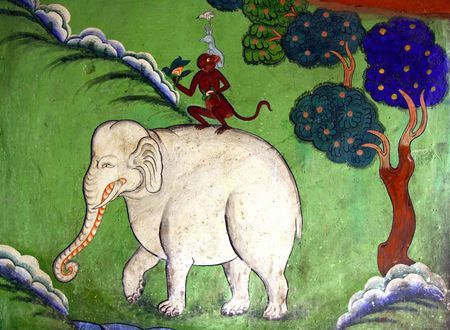

While I would meditate throughout the night, mice and rats would come and sleep on the pillow next to me. For my stretch of ten hours, I would sit there unmoving even if they jumped into my lap. Not that I had any particular affinity towards them, I just wasn’t prepared to disturb, much less abandon, my meditation for a bunch of rats. At first, it had felt awfully gross to have rats hop around me but over time, I’d developed a sort of friendship with them. They were my companions and the same God dwelled in them.

“You could do with some meditation,” I murmured to the one who was hiding close by, darting glances back and forth and trying to anticipate my movements. One thing meditation immediately checks is the restive tendencies of the mind.

For the whole of the seven months I was there, the rats would not spare anything. Not even my only shawl, or the spare batteries of my torch. I had a small bottle of clove oil, they took away the whole bottle in the first week. It was a small bottle though, about the size of my thumb, and the wild rats were bigger than their city cousins.

The rats dug into everything – the wooden planks that made the walls of that hut, the mixture of cow dung and mud that had filled some of the gaping holes, the thatched roof, a couple of polybags that served as my makeshift tarp stuck in the roof to prevent it from leaking. They gnawed at anything they could sink their teeth into.

Yet, these aggressive rats never destroyed my bedding comprising my only quilt, mattress and two pillows (I used to sit on one pillow and keep one on the side). As if they knew that it would be extremely difficult for me to function without my bedding. Other than a quiet mind, it was the only comfort I had in that dilapidated cow shed held together by wooden planks, tarp, cowdung and hay.

The rats never harmed me, not even once. But most of all, they never went even close to my mandala, the mystical Sri Yantra. Not even once they nibbled on the red cloth that covered it when not in use or the actual paper itself. As if they knew that this wasn’t just a piece of paper but a field of energy, pure and at once divine.

At times, I felt they were just being playful, testing me, teasing me, joking with me. Nature does all that with the one who seeks to rise above it. Before she empowers you with bliss and insight, with siddhis and abilities, she makes sure that you are the right recipient. Too much is at stake. One wrong man, one Hitler, can cause irreparable and eternal damage to the whole of mankind.

I lifted the little door – a makeshift door made by nailing together a few pieces of wood – and put it to the side. I bent in half and stepped outside. The soft radiance of the moon had barged into the darkness of the winter night. The light had jostled its way out of love lending a sense of completeness to the whole of creation, as if to prove that light and darkness can coexist. This duality is the beauty of our existence. Joy and sorrow, heat and cold, good and bad, they coexist. A state of perfect inner serenity, free from the ripples of selfishness, that arises from meditation not only helps you live through the contradictions of life, but actually appreciate them.

It was snow all around sparkling beautifully under the tranquil moonlight. The trees were quiet as if the boughs and leaves were sleeping too. An icy breeze blew gently. My ears and nose froze within the first minute. At a distance, I heard wild animals move suddenly, as if startled by my unexpected presence.

A deer grunted loudly and another made a high-pitched ‘baa’ sound. In an instant, the large field was abuzz with a lot of activity. Wild boar made a mix of snorting, squealing and grating sounds and ran upwards to the hills. The bucks and does galloped towards the woods. Other animals, probably a bear, at a greater distance, also moved into the woods.

That night, they were more visible than most other nights, for tonight it wasn’t just a full moon but a clear sky as well–a rarity in the past three months with frequent storms, rains, snowfall and hail. The whole field ahead of me glittered like it was God’s playground made from silver-dust.

It was pure bliss to see those wild animals move around.

I felt no fear (fearlessness is a natural byproduct of good meditation). I was in love, one with everything around me. The Vedas call it advaita. Fear only arises in duality, in a sense of separation, that somehow you may lose the other one or that they may harm you. But who can harm you when there’s only you around? There’s no fear in a divine union. This state of perfect union is the final stage of meditation. In this state, meditation ceases to be an act. Instead, it becomes a phenomenon, a state of mind.

These beautiful beings of the wild were merely an extension of my existence. It is here that you are not afraid of your own body. Like everything in the universe, all the wild animals around were nothing but my own reflection. They were my past lives. I had been a boar, a bear, a deer, a tiger. Everyone and everything around you was once a part of you or you were a part of them.

The sum total of all we have ever been over the billions of years, across myriad life-forms, is eternally present in us, with us, around us. At all times. It’s not just a matter of saying. If you continue to walk the path of meditation, one day you’ll experience, know and understand the truth in my words.

I reached out to the roof and picked up some snow. It was more hardened than usual because it wasn’t fresh snow. It was from the previous night. At any rate, it was delicious. It would soothe the excessive heat generated in my body due to intense meditation. The subtle vibrations had gradually turned into deep sensations coursing through my entire body and intensifying in my head like waterfalls and streams running through the Himalayan hills and vales stumbling into the Ganges. The sensations in my head were beyond bear or expression. I hadn’t yet learned how to get rid of these acute sensations.

A superb clarity of mind, of the senses, of the past, present and future coursed through the river of my consciousness. Sometimes I didn’t want those sensations for they would render me completely useless to do anything else at all. Even the simple act of putting a tilaka on my forehead after I bathed would become a challenge.

All I could do was meditate and whenever I meditated they would continue to build up to the degree that I felt as if my body was not made from flesh and bones but it was simply a conduit of sensations, a container of energy. The container itself was made from nothing but energy. I pulsated as if there was no physical reality to my own existence. And yet, the body was governed by the laws of nature so I had gone through my fair share of pains and aches. Those aches, however, only intensified my resolve to persist with my meditation so I could go beyond the shackles of this body.

Merely knowing that this body is simply a vehicle, or that we hold within us an entire universe, is incomplete knowledge. It is wisdom without insight and doesn’t lead to bliss but ignorance. I say ignorance because you end up forming these concepts without any experiential understanding. The rigors of meditation aren’t for the faint-hearted. Above everything else, in the beginning stages, it requires extraordinary patience and self-discipline.

I had moved deep into the Himalayan woods seeking even more intense solitude. A few villagers had come all the way to see me on the last day of my meditation in the woods. When I emerged from my hut seven months later, they were startled. They thought a very weak and frail sadhu would come out from the hut for I’d lived on very little for more than seven months in extreme conditions. Sometimes, I would step out in the dead of night and eat snow.

I had not seen my own face for months. Looking in a tiny mirror, I used to put the tilaka on my forehead once in 24 hours after bathing with icy cold water. That mirror was too small to render a reflection of my entire face. I didn’t know how I looked. I knew I had lost weight but I didn’t feel a lack of energy.

They were startled because there was not even the slightest sign of physical weakness or any fatigue at all. For a moment, even I was surprised to look at my own face, the light in my own eyes, only momentarily though. For, I knew that my soul, free from all ties of relationships, religion and the world, was soaring high in the infinite universe of bliss. My source of energy was no longer the food I consumed but the thoughts I thought. And, I didn’t think of anything. I’d been thoughtless for a long time now. Any thoughts I had were only of God or love.

What happens when you churn milk? It turns into butter and once done, it never goes back to being milk. If milk can stay for a few days before going sour, butter can stay fresh for a couple of weeks. If you heat up butter it becomes ghee, and ghee can remain unaffected for years. No matter how you treat it, it can never become butter or milk again.

The final state of bliss is akin to becoming ghee from milk – it’s irreversible.

I had never wanted to come down from the Himalayas. That extraordinary bliss was beyond what I can ever explain. Hundreds of times I had heard the unstruck sound in my heart. Countless times, I had felt myself going out of my body to be wherever I wanted to be. On numerous occasions, I heard the most beautiful sounds, had the most magnificent visions. My world was complete. There was no need or the urge to come back. On the contrary, I wanted to drop my body.

But realization changes in you something irrevocably. You no longer just think about yourself. Even if you have no responsibilities or family, you can’t just do whatever makes you happy. Somewhere, you recognize that you’ve been blessed in the most potent manner and that it is your duty to share your bliss with those who seek it.

No matter how much you may want to disregard it, you feel obliged to live for the world around you. Like a cow finds joy in feeding its calf, you find your joy in serving humanity. No matter how the world treats you, you never stop being compassionate. It happens naturally, that you end up putting others’ interests before your own. In your selfless conduct you discover your greatest happiness.

Something miraculous happens to such a selfless person. The forces of the universe sit by your feet waiting for your command. You can’t be selfless unless you start to see everyone as part of you and you as part of everyone else. Until you gain an insight into that oneness, you treat yourself differently from others. But, once you gain an experiential understanding (not merely an intellectual one) into the true nature of your mind and everything around you, an ever-brimming compassion arises naturally for all sentient beings.

Any attainment is worthless if it doesn’t help our world move forward. Any meditation is pointless if it doesn’t expand your consciousness, if it doesn’t amplify your existence and bring about in you compassion, positivity and love. That’s what meditation is about. This has been my journey.

Go, embark on yours.

This is the epilogue from my latest book on meditation: A Million Thoughts.

I chose to share the epilogue because the beginning chapters you can read anyway using Amazon’s Look Inside feature. A detailed book on meditation, it’s being released by Jaico Publishing House. Here are some relevant links to get this book:

- Amazon India. (If it says unavailable, just check back in a day or two.)

- Paperback on amazon.com, e-book on amazon.com (For all readers outside India).

Finally and importantly, my immense gratitude to those who post honest reviews on Amazon. I personally read every single review. Thank you very much. Really.

Peace.

Swami

A GOOD STORY

There were four members in a household. Everybody, Somebody, Anybody and Nobody. A bill was overdue. Everybody thought Somebody would do it. Anybody could have done it but Nobody did it.

Don't leave empty-handed, consider contributing.It's a good thing to do today.

Comments & Discussion

16 COMMENTS

Please login to read members' comments and participate in the discussion.