The Man Who Fasted

Why do we pray? Should we bother at all when life remains inconvenient anyway?

The Three Most Important Decisions

Our life is shaped by the decisions we make. But there are three decisions in particular that set the course of your destiny.

It Seemed Like a Good Idea

If you could go back in time, would you really do anything differently? Could you, even if you tried?

Socrates and Ripped Jeans

Plus announcing the launch of Tantra Sadhana

powered by AI

Virtual Retreats

Immersive Courses - Pay Whatever You Like

Self-Purification

A 15 days discovery of the self

Learn Vishnu Sahasranamam

Master the Vedic Chanting of Vishnu Sahasranama

The Art of Meditation

Learn meditation in four days (and master it over a lifetime)

Devi Bhagavatam – Hindi

Five days of Immersive Devi Bhagavatam in Hindi.

Kundalini Meditation

Learn Kundalini meditation and all the kriyas associated with it.

Vedic Astrology – English

Learn the Ancient Art of Vedic Astrology at your own pace. In English.

Vedic Astrology – Hindi

Learn the Ancient Art of Vedic Astrology at your own pace. In Hindi.

Awesome Books

21 delightful reads to choose from

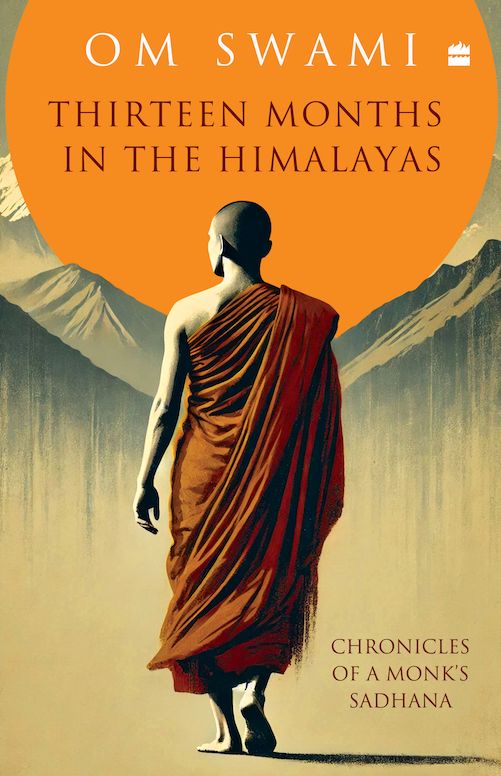

Thirteen Months In The Himalayas

‘If you won’t get Her vision, who will?’ With these words from Bhairavi Ma echoing in his heart, a young monk who had renounced a multimillion-dollar business empire retreated into the Himalayas. For thirteen months, he engaged in intense meditation, … Read more →

The Legend of the Goddess

“If there’s only one sadhana you could do to invoke the Goddess of opulence, it would be the one of Sri Suktam,” says the bestselling author Om Swami. Emerging from the sixteen sacred verses of the Rig Veda, Sri Suktam … Read more →

Bhagavān And Bhakta

‘Never turn your back to the ocean,’ the wise say. Whether that be the real blue sea or the ocean of grace, you want to be facing it, ready to take it all in when the tide turns your way. … Read more →

The Rainmaker

Healing is something which only Divine Mother does. Healing is something which only Mother Nature does. I am simply someone who is getting the opportunity to deliver some right messages. And that’s what it really is and that’s what I … Read more →

A Random Post

See what Providence wants to tell you today