Objects in Mirror Are Closer Than They Appear

Just a bit more of Om Swami musings...plus the Guru Poornima event

Being Ordinary

Here's a beautiful Taoist story with profound wisdom

Crippled

We don't have to let our shortcomings become our limitations. Here's a true story.

The Clever Adulteress

Here is a beautiful story with a profound esoteric meaning.

powered by AI

Virtual Retreats

Immersive Courses - Pay Whatever You Like

Walk The Dragon: Leadership Program

A seven-week powerful program for managers, entrepreneurs and people with passion.

Self-Purification

A 15 days discovery of the self

Learn Vishnu Sahasranamam

Master the Vedic Chanting of Vishnu Sahasranama

The Art of Meditation

Learn meditation in four days (and master it over a lifetime)

Devi Bhagavatam – Hindi

Five days of Immersive Devi Bhagavatam in Hindi.

Kundalini Meditation

Learn Kundalini meditation and all the kriyas associated with it.

Vedic Astrology – English

Learn the Ancient Art of Vedic Astrology at your own pace. In English.

Awesome Books

20 delightful reads to choose from

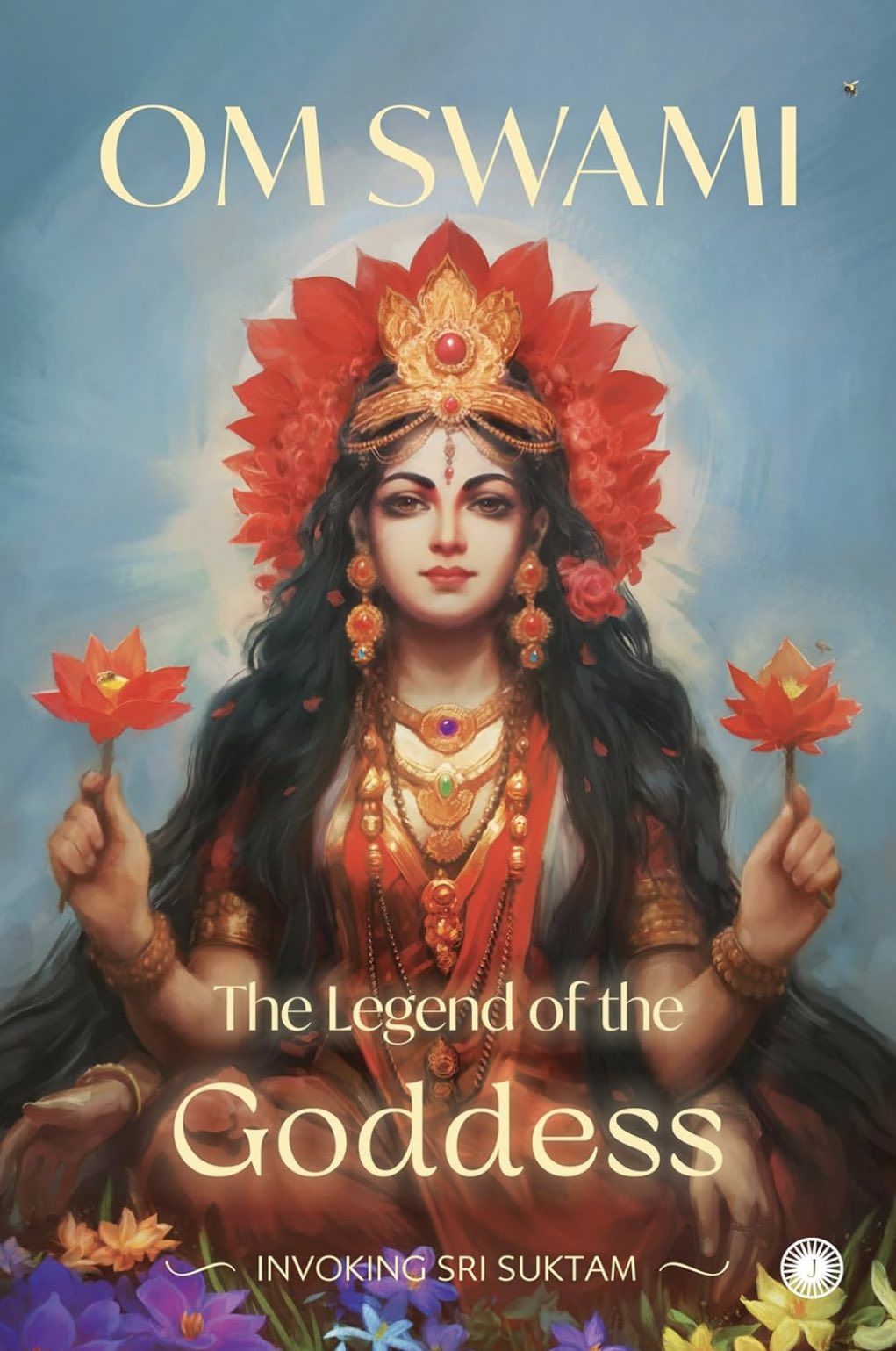

The Legend of the Goddess

“If there’s only one sadhana you could do to invoke the Goddess of opulence, it would be the one of Sri Suktam,” says the bestselling author Om Swami. Emerging from the sixteen sacred verses of the Rig Veda, Sri Suktam … Read more →

Bhagavān And Bhakta

‘Never turn your back to the ocean,’ the wise say. Whether that be the real blue sea or the ocean of grace, you want to be facing it, ready to take it all in when the tide turns your way. … Read more →

The Rainmaker

Healing is something which only Divine Mother does. Healing is something which only Mother Nature does. I am simply someone who is getting the opportunity to deliver some right messages. And that’s what it really is and that’s what I … Read more →

The Big Questions of Life

Pain is inevitable; suffering is optional. Loss is unavoidable; grief isn’t. Death is certain. And life? Well, life isn’t certain. Its uncertainty, unpredictability, even its irrationality, make it what it is. Often, we run blindly into fire, we step on … Read more →

A Random Post

See what Providence wants to tell you today